In 1979, KidsPeace (then Wiley House) received its first license to begin providing foster care services to children at the Bethlehem, Pennsylvania office. It was during the 1970’s when Wiley House expanded their continuum of services to include day treatment services, specialized preschool services, afternoon treatment programs, and foster care.

I have been privileged to work with the Foster Care and Community Program at KidsPeace for nearly thirty of its forty years. I can reflect on the many children, families, and associates who have been a part of the KidsPeace program during this time. It is in looking at the legislation and changes within the foster care and child welfare system that we see the progress from those early days to the present.

“Progress is impossible without change, and those who cannot change their minds cannot change anything.” – George Bernard Shaw

The stage for foster care was set with the passage of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) of 1974. CAPTA provided minimum standards for defining physical abuse, neglect and sexual abuse. States increased programs for the prevention, assessment, investigation

and treatment for children. With an increase in the number of child abuse and neglect reports, the needs for foster care programs grew as a means to provide a temporary service to children and families.

The CAPTA Reform Act (1978)continued to promote the development of children who would benefit from adoption, and extended and improved CAPTA. The Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act (1980) required states to make adoption assistance payments to families. It also required states to make “reasonable efforts” to prevent removal and to reunify families.

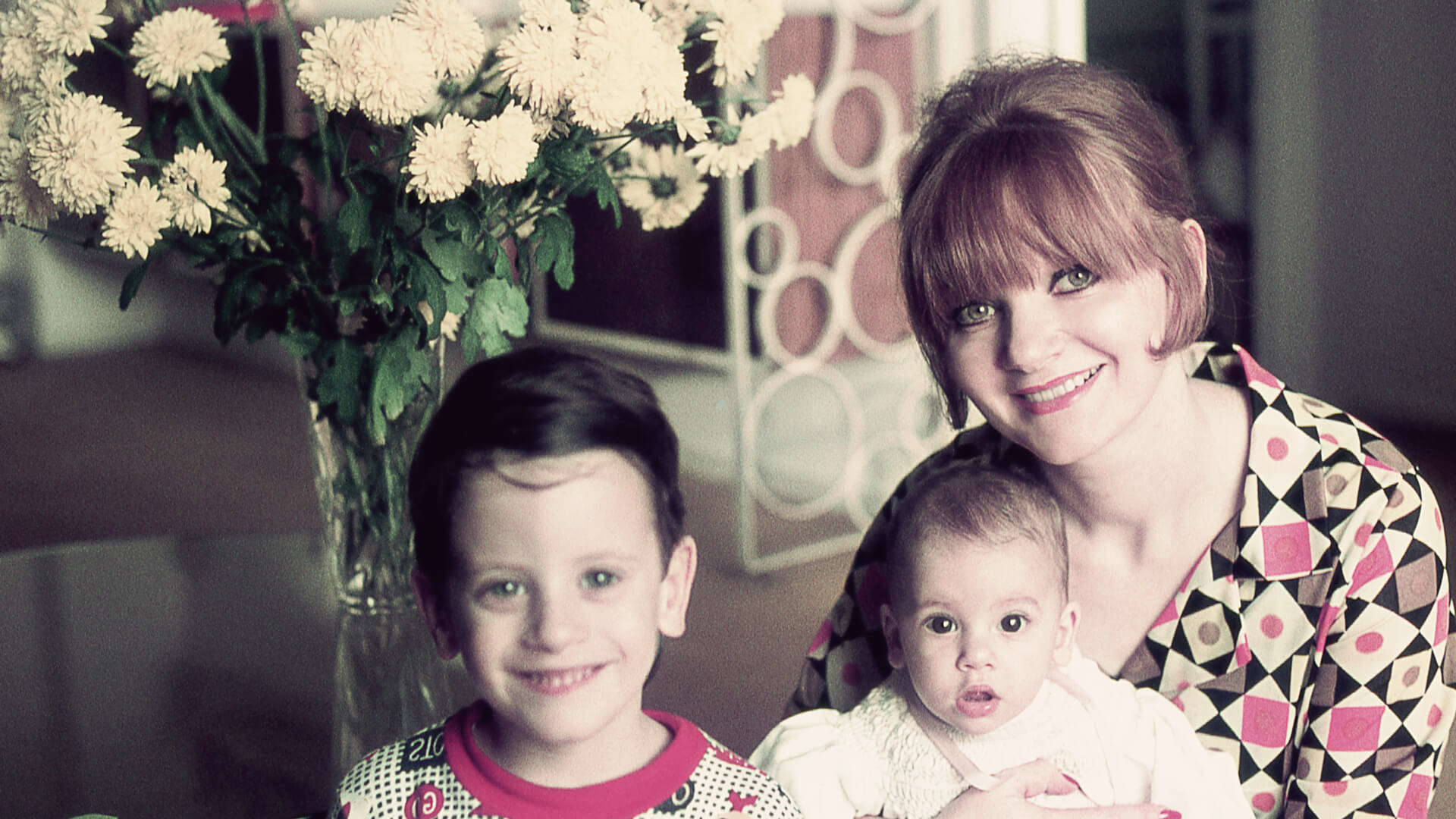

In the Wiley House Community Care Manual, the foster care program was designed to “build on the strength of the family model rather than the medical or social rehabilitation models in utilizing the strengths proven effective in our existing programs.” A teamwork approach used professional staff of social workers, therapists, and clinicians to work closely with the foster parents in the development of therapeutic treatment goals. The program grew to include additional recruiters/trainers to prepare potential foster families.

During these years, the primary focus had been on family reunification. While reunification did occur for many children, some children continued to linger in foster care for longer periods of time. Other societal factors led to an increase of children at risk of child abuse and neglect. Poverty, homelessness, substance abuse, declining informal and extended family supports put a strain on the ability of families to receive prevention and early intervention services along with needed treatment for mental health and substance abuse.

In 1997, the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) looked to restore some balance between the rights of parents with the safety of children. Safety of the child was a guiding principle in determining any decision to remove or return children with a family. ASFA looked to accelerate permanency for children. In most cases, court proceedings to free a child for adoption could occur for children who had been waiting in foster care for at least 15 of the most recent 22 months.

Concurrent planning was instituted to shorten the length of foster care placement. In addition to pursuing reunification with immediate birth family, the team began to explore other options, such as extended family (kin) and foster parents as a permanent resource to children.

Children benefitted from shorter stays in foster care and fewer moves. Foster families who had bonded with children became adoptive resources. Training for resource parents was expanded to include resiliency theory, attachment, and trauma-informed care.

Additional changes resulted with the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoption Act (2008). The definition of kinship was expanded to include extended family and friends. The act required that extended family members be identified and questioned about their willingness to be a resource for children entering out-of-home placement. Kinship parents could be approved as resource families and receive the same subsidies as a foster parent. The act also required that agencies place siblings together unless specific concerns were identified. Other elements to foster connections are to keep children within their “home” school. A final part of the act addressed the needs of older youth. Extended benefits were given to teens beyond the age of 18. Youth could elect to remain in foster care until the age of 21 as long as they were in school or working.

With this Act, the children often experienced less trauma by remaining with siblings or family members. By staying in the home school, education disruption is avoided and better outcomes could be achieved. Resource parents have taken on new roles of being mentors to birth families which results in faster reunification.

Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act (2014) brought further changes. This act looks to keep children from becoming victims of sex trafficking. It gives children age 14 and older authority to participate in the development of their own case plans. The act also looks to promote a sense of “normalcy” for children in out-of-home care. By defining a “reasonable and prudent parenting” standard, resource parents are trained and allowed to make decisions for opportunities for youth to engage in age- and developmentally appropriate activities.

As a result of the Prudent Parenting standard, many more foster children are easily engaged in activities like going on vacations, spending time in the community, participating in activities, working part-time jobs, and even obtaining a driver’s license. Resource parents, after discussions with caseworkers, have clear guidelines in making decisions for children in care. The goal is to provide youth with necessary life skills and opportunities as they enter adulthood and independence.

What’s next for foster care? Family First Prevention Services Act (2018)was signed into law last year, and state agencies are working on its implementation. Family First looks to balance the allocation of funds to child welfare programs. The first part looks to improve prevention services to keep at-risk youth from entering foster care. Prevention programs would be used for 12 months. The second part looks to limit the amount of time a child would be placed in congregate care, such as residential or rehabilitation placements. Guidelines are established for qualified residential treatment programs, and regular reviews are completed. The third part of the law looks at foster care and adoption. While prevention services may lower the number of children entering foster care, youth may be entering care because of shorter stays in residential care. The law says that individual states will have to look at their licensing standards for programs. Increased family support services under the law will include the strengthening of foster and adoptive families. Foster home recruitment and retention will be critical to serve the needs of children who are unable to either live with immediate family or relatives or who do not qualify for extended congregate care.

The immediate future is moving to more outcomes-driven, family-focused care. Here in Pennsylvania, the Office of Children, Youth, and Families is targeting four areas. OCYF wants to safely reduce the entries of children into out-of-home placement. They also want to promote safe and stable reunifications for children and families. Third, they want to achieve timely permanence for children in out-of-home care. The last effort is to enhance prevention and stabilization services.

In 2018, KidsPeace Foster Care and Community Programs served 1,233 children across seven states. FCCP conducts standardized outcomes measurement using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. The SDQ is administered on intake and at discharge for youths. An outcomes report for 2018 showed 73% of children in foster care were discharged to equal or less restrictive placement, often reunification with birth family or kin. Another 13.6% of children achieved permanency through adoption. Other outcome studies have been tracking the educational outcomes for children in placement.

In our foster care programs, we also ask our clients, their families, and our staff to complete a survey called the Trauma-Informed Agency Assessment (TIAA). The TIAA was developed to measure the extent to which agencies employ trauma-informed approaches in meeting the needs of our clients and their families. With the insights we gain through the TIAA, we are able to develop actionable plans which help us to improve our responsiveness to trauma in our clients – trauma which can impact their physical, emotional, behavioral, and cognitive development.

Evidence-based training, policies and practices are already appearing in KidsPeace FCCP programs. “Together Facing the Challenge” (TFTC) is a training curriculum developed by faculty of Duke University’s Services Effectiveness Research Program in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. TFTC is one of only two therapeutic foster care programs in the nation that has received a rating of “Supported by Research Evidence” from the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare.

Utilizing research and data from observations studies of therapeutic foster care in the KidsPeace FCCP program in North Carolina, developers established a series of structured didactic and interactive training sessions for parents and program staff to provide them with the tools and skills necessary to improve outcomes for youth in care.

Three factors have led to TFTC’s success in foster care:

- TFTC builds upon supportive and involved relationships between supervisors and foster parents.

- TFTC uses effective behavior management strategies by foster parents.

- Finally, TFTC uses supportive and involved relationships between foster parents and youth in their care.

By the end of 2019, KidsPeace FCCP offices in all states are aiming to be certified in TFTC. We have been training our resource parents and KidsPeace associates in TFTC practices, and feedback from parents has been positive. TFTC has provided parents with the tools to manage the therapeutic needs of children impacted by trauma. It also gives everyone on the treatment team a common language to discuss the goals and challenges. Ongoing communication and feedback between offices has been helpful in successfully implementing the program.

By using an evidence-based program, KidsPeace FCCP looks to achieve even higher outcomes for children in care. The laws and regulations of the past forty years have steered the direction of foster care services. As we look ahead, KidsPeace FCCP follows the KidsPeace Vision to help children and families transform their lives.

KidsPeace Vision

To transform

lives of individuals with emotional, mental, developmental, and behavioral disorders caused by trauma, abuse, neglect or other causes; by providing mental health care and educational services in a safe environment with teamwork, compassion and innovation.

References:

KidsPeace® The First 125 Years: Giving Hope, Help and Healing to Children Facing Crisis

Wiley House Community Care Manual

Historical Child Welfare Information Gateway Timeline on Foster Care and Adoption https://www.childwelfare.gov/aboutus/cwig-timeline/CliffsNotes on Family First Act, John Kelly, https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/finance-reformBuilding a Child Welfare System for the 21stCentury, Jennifer Jones & Theresa Covington, https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/finance-reformMajor Federal Legislation Concerned with Child Protection, Child Welfare, and Adoptionhttps://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/otherpubs/majorfedlegis/Pennsylvania Council of Children, Youth and Family Services: Child and Family Service Review (CFSR) and Findings and Program Improvement Plan (PIP), March 18, 2018.

From Theory to Practice: One Agency’s Experience with Implementing an Evidence-Based Model. Maureen Murray, Tom Culver, Betsy Farmer, Leslie Ann Jackson, and Brian Rixon. J Child Fam Stud. 2014 July; 23(5): 844-853.