As a journalist and author, I’ve spent most of my life writing stories. But now, as an entrepreneur, I find myself in an office building in Harvard Square where my team is writing code. Along with 100 or so pilot users, we are testing a new device to help reach and communicate with children who have autism.

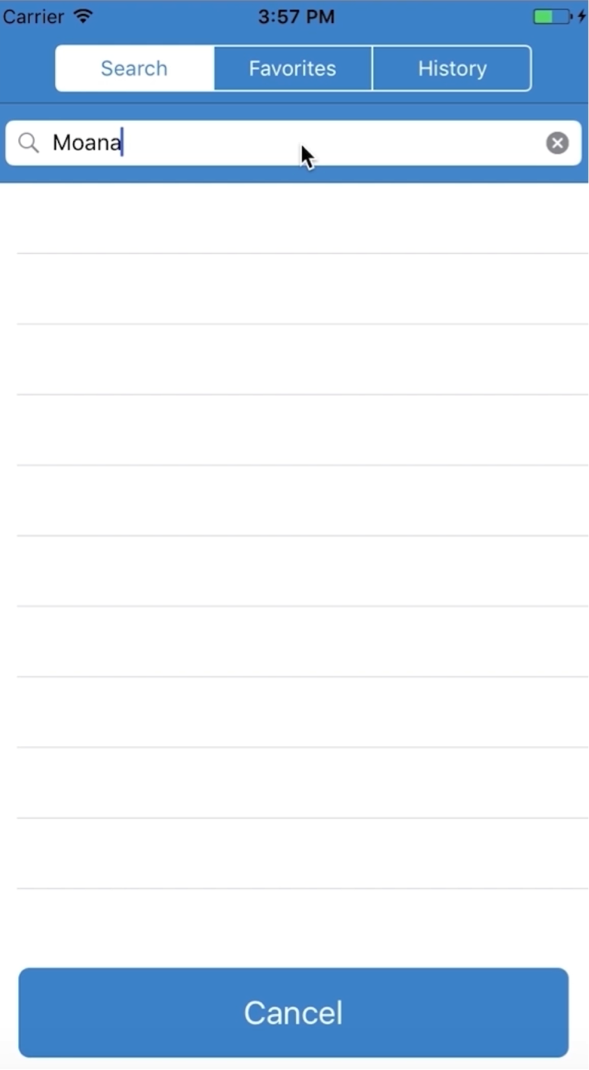

Our new tool, called ”Sidekicks,” is designed to help people connect with a child who has autism through the child’s passion, be it Disney movies, Legos or train schedules. Our hope is that Sidekicks will give children with autism a voice by building on their own interests.

(Full disclosure: I’m founder and chief executive officer of The Affinity Project, the company that produces Sidekicks.)

The origins of this effort date back more than 20 years. That’s when my son Owen was diagnosed with autism and lost all speech. He was just shy of 3 years old.

Our lives became dominated by the acute necessities known to millions of parents of children with autism: Find clinicians and therapists, pay unreasonable bills, reorder expectations, redefine the length of a day, and redirect virtually every feature of our lives. The overriding necessity was to find a way — any way — to connect with Owen.

I have told the story of what unfolded, first in my 2014 book “Life, Animated,” and then in the Academy Award-nominated documentary of the same name. Once my wife, Cornelia, and I realized that our son, at age 6, had silently memorized dozens of Disney animated movies, we began to communicate with him in Disney dialogue. Throw him a line, he’d throw you back the next one. Night after night, we became animated characters, playing scenes to fit every occasion and emotion.

There was plenty of speech, language, occupational and play therapy as well as basic tutoring during this period. But we saw that progress was clearly linked to tapping, and joyfully validating, Owen’s ”circumscribed interest” — a term that Leo Kanner used in 1940s and ’50s for restricted interests, a signature feature of autism1.

Love what he loves:

The view since then has largely been that these interests are obsessions, nonproductive and perseverative, and part of autism’s core features. Cut them off, reduce their frequency, or use them as a reward in behavioral therapies. Whatever you do, don’t feed them.

Well, we did. Disney films became our pathway to reach into his world and, importantly, to help him reach out to ours. Over several years, Owen’s speech steadily grew, with usages drawn heavily from movie references. He learned to read largely by reading the films’ credits. During his teen years, we worked with therapists to develop techniques that were effective in helping our son apply his passion to social, emotional and cognitive growth.

Like parents of children with autism everywhere, we worked tirelessly to ”fix” Owen — to build skills he desperately needed to taste human contact, and be as independent and self-sufficient as possible. Yet it was a joy-based philosophy that guided us, summed up by Cornelia’s single line: “Love what he loves is the way we’ll love him.” Through this particular sort of love, capacity grew.

During the reporting of the book back in 2013, Cornelia and I discovered something startling: Circumscribed interests have received only fitful study since the days of Kanner, even though an estimated 90 percent of those with autism have at least one of them2. In our household and in the book, we gave them a new name – ”affinities” – which seemed to us a more appropriate term. This term bespeaks inclination, passion, expertise, self-identity and, importantly, choice. We called what we did with Owen “affinity therapy.”

After my book’s publication, the term caught on. Cornelia and I were swamped with calls and emails from hundreds of parents reporting a wide array of affinities — Harry Potter, maps, astronomy, washing machines, wind-chimes or Minecraft — and urgently asking us how they might do what we’d done. Many felt affirmed — they had been right all along — and also anxious about how to move forward. As one mother said to me, “My husband and I both work out of the home, and I can’t spend 10 years in the basement watching Star Wars. How do we manage to do this?”

Code breakers:

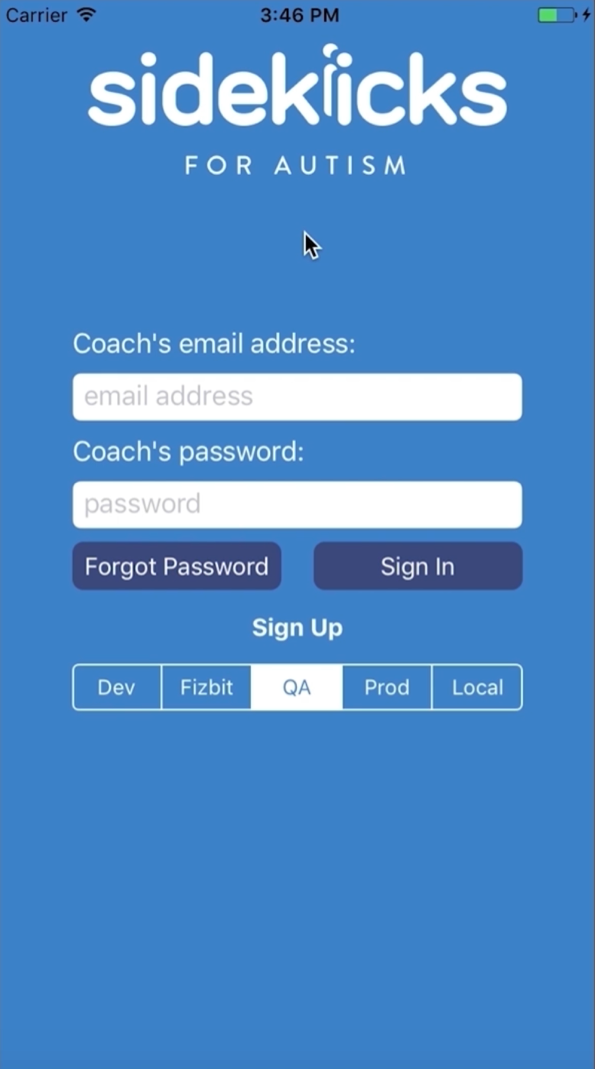

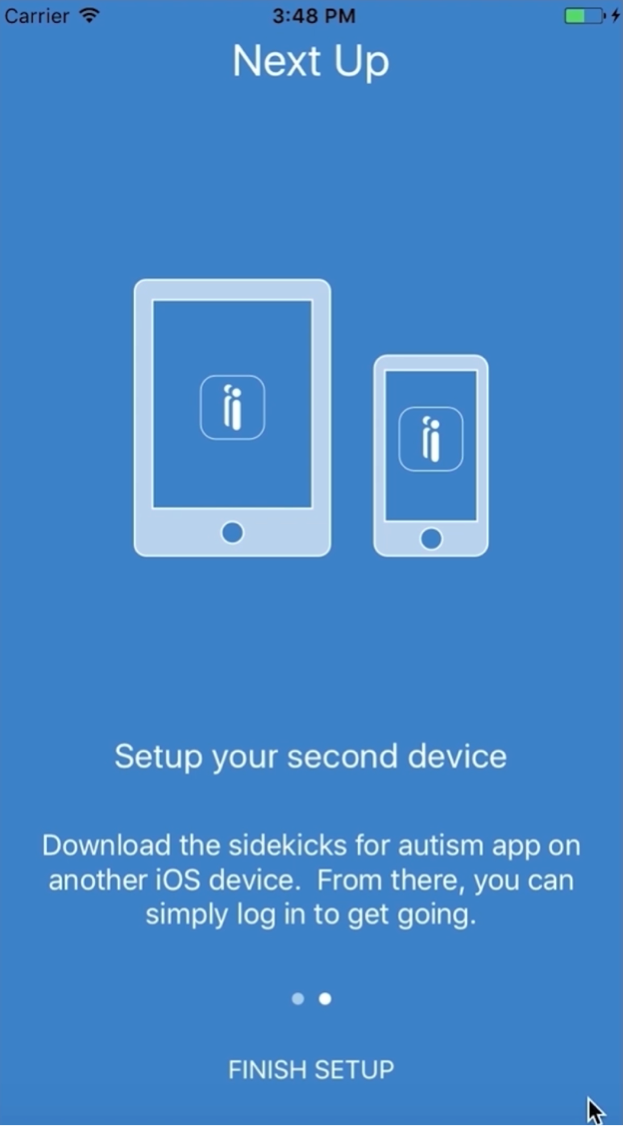

In the summer of 2014, I met with the inventor of Siri in Silicon Valley. Meetings with other leading technologists followed. By year’s end, we’d formed The Affinity Project and had filed a patent for a ’guided personal companion,” which would become Sidekicks.

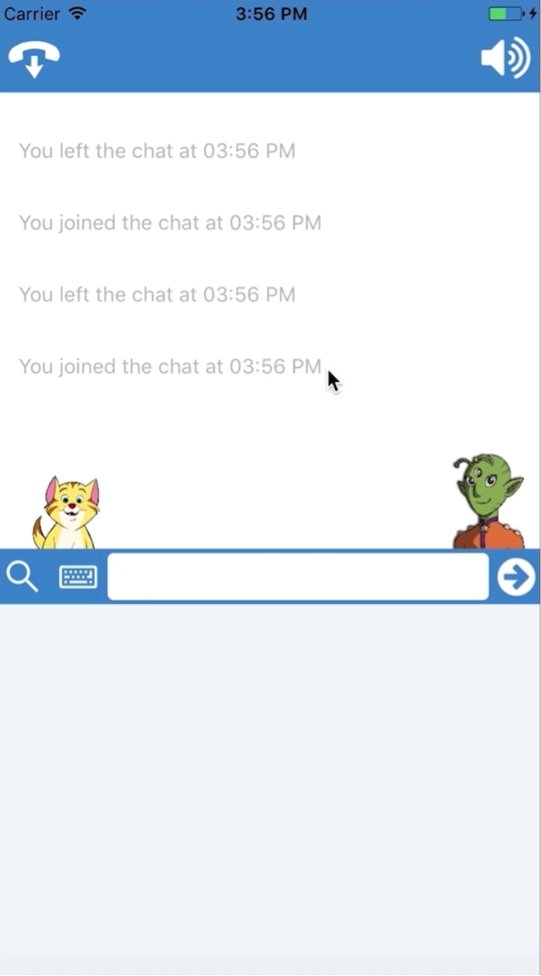

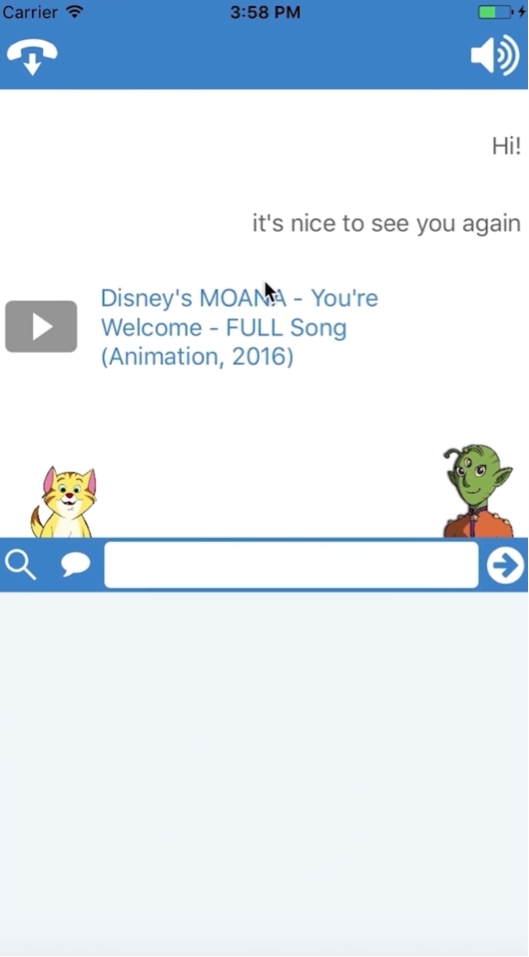

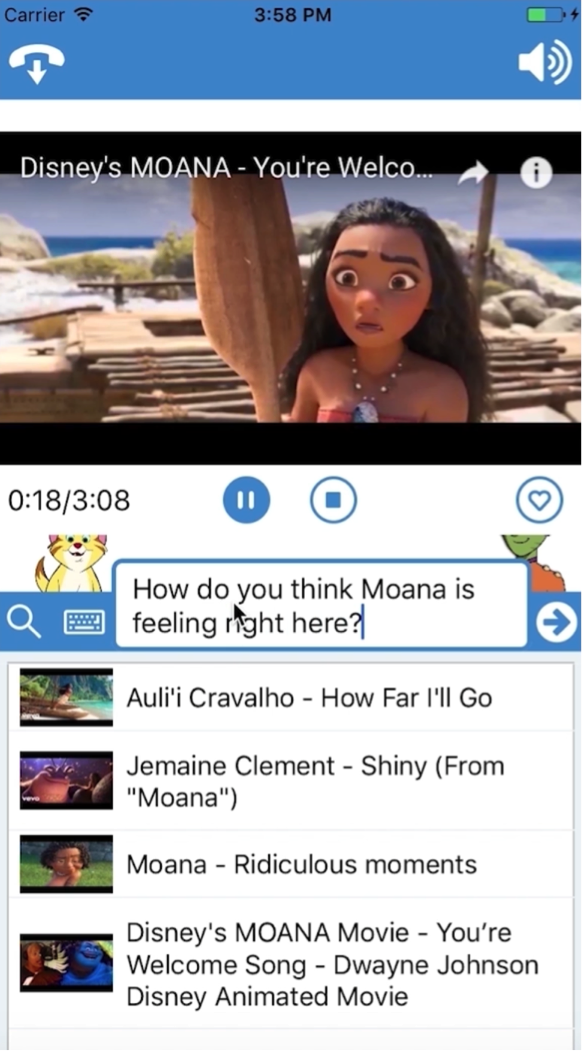

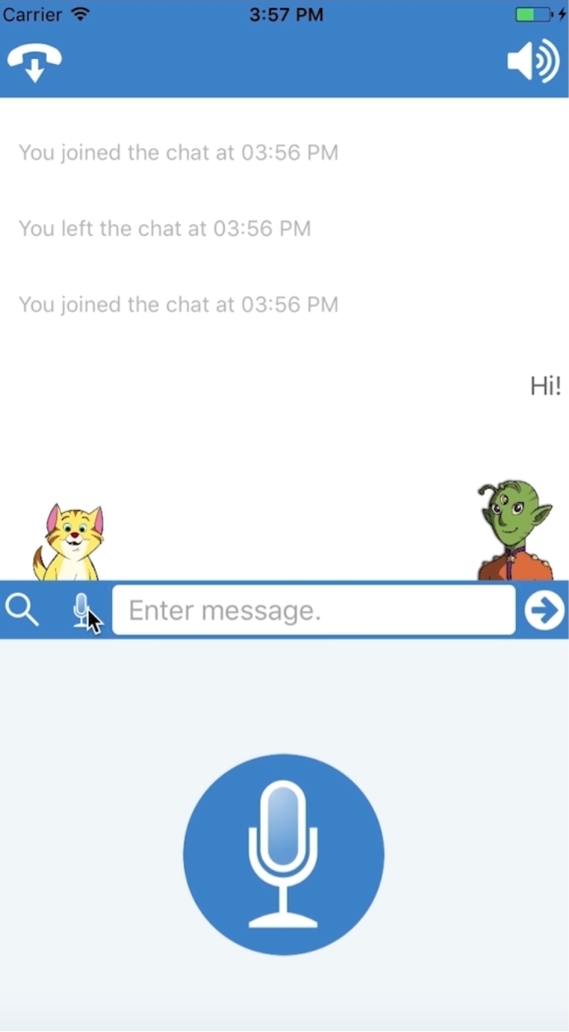

Talk or type into your phone or computer and the words come through in real time in the voice of an animated character on the child’s phone or computer. When the child responds, you can hear it and answer. Rich media, such as movie clips, can be streamed between the connected devices to tap the child’s affinity.

With the human-infused Sidekick as a guide and companion, a child’s passions can become pathways for engagement, expression and growth. For example, if a child feels kinship with Velociraptors — “pack animals,” as one young lady recently told me, “who taught me about how we need to work together and rely on each other” — she might share a clip or link about Velociraptors. Then the parent or therapist has a precious handle with which to discuss friendship or reliance on others in the child’s real life.

Most of the children, nowadays, have video-based affinities, and watch videos about their favorite topics extensively on YouTube. That’s an ocean of content to work with.

That’s what 100 or so families have been doing over the past year in a pilot study of the use and effectiveness of the app. They’re finding new ways to connect with their children and helping the children use strengths, wrapped around their affinities, to help themselves. Early results are encouraging, showing that the tool supports language growth, emotional identification and social skills development. There are several hundred families on our waiting list. The study will soon expand to accommodate them.

One of our advisers is Kevin Pelphrey, an autism researcher at George Washington University, who has a daughter much like Owen. Pelphrey wrote in a 2015 research proposal that people with autism use their affinities “like Enigma machines, to help decipher an otherwise incomprehensible social world.” They rely on affinities as “code breakers,” he says, to crack the codes of themselves and the world around them.

It’s an elegant term, and appropriately applied. As a survey published last month showed, many people with autism view their affinities as calming and often useful3. Of the 80 adults in the study, most said that their job or educational program involves their affinity, and that their preferred interests help with their anxiety. The Affinity Project, in collaboration with Autism Speaks, has just launched a large survey of people with autism to determine the prevalence and importance of affinities among this population.

Evolving conversation:

The key is to create a naturalistic and evolving conversation, sometimes led by the parent- or therapist-infused avatar, sometimes by the child. A feature now under construction allows parents to follow their children on their internet searches. When a child searches for something on his phone, a URL and metadata will appear on the parent’s phone. The parent can see what enlivens the child and then have the Sidekick join the child on his phone to discuss what he finds most interesting.

After a few exchanges in these areas, our dialogue-management system begins to generate automated responses and — based on a situation the child encounters or a need he expresses — even initiate conversations. The parents or therapists are needed less and less, even as the avatar carries their essence.

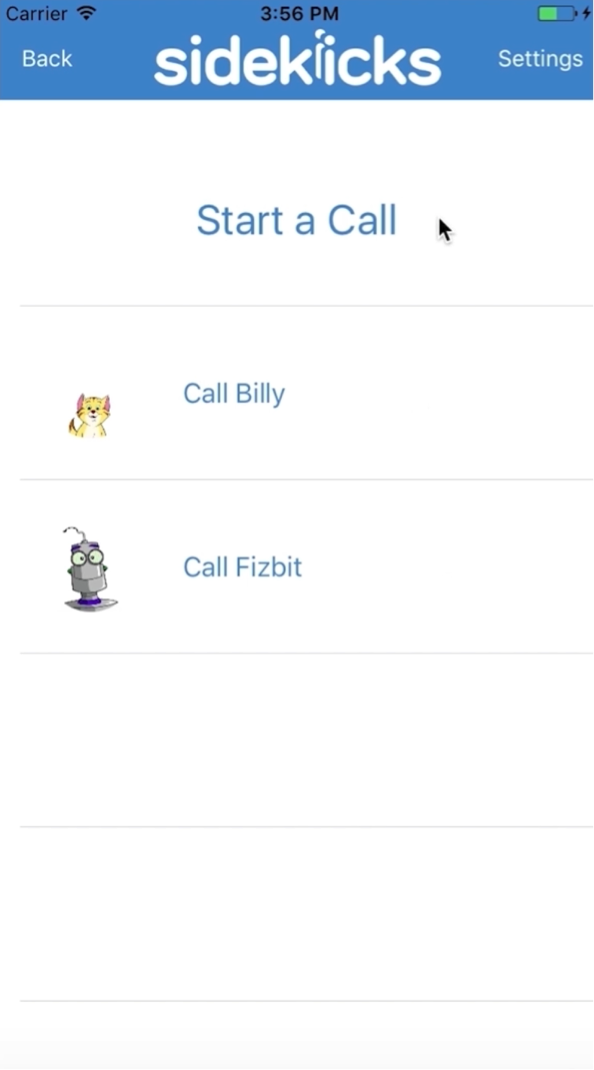

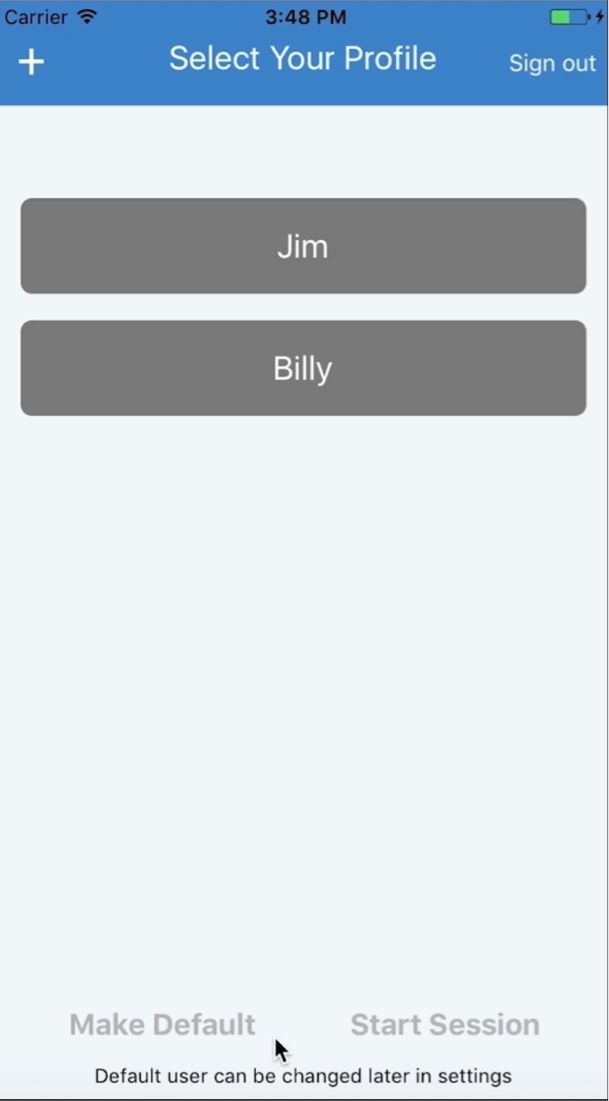

Through a new Sidekicks feature, someone vetted by the parents can also jump behind the curtain and guide the avatar. Parents schedule a time with a ‘coach’ they select from our roster, hand the phone to their child, and leave the child to engage with his Sidekick. The coach takes the burden off parents, although some parents choose to sit with their child during the session.

One mother, who schedules daily sessions after school for her 14-year-old son, reported that his echolalia (meaningless repetition of words) gave way to receptive and expressive language over 15 sessions. Our servers captured these exchanges — as they do all utterances — and she can now show it to her son’s therapist. Parent reports are notoriously uneven, leaving both therapists and the parents frustrated. Now, parents can share their data, and analytics can track progress.

It’s about joy:

The volume and precision of the data may form a deep foundation for research. Clinicians at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston plan to measure the platform’s efficacy. They aim to establish baselines for language and emotional processing for 30 children and give 15 of them three months of affinity-focused therapies using Sidekicks. The team plans to measure growth in emotional regulation, expressive speech, social communication and problem-solving in all the children, laying the groundwork for a large randomized controlled trial.

John Gabrieli’s team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology plans to use brain imaging to map the areas that affinities activate. This will be the first study of its kind to demystify the neural underpinnings of these special interests. The team plans to enroll 40 children who will lie in a scanner as they complete a simple task and are rewarded with either their affinity or money. The goal is to discover the neural pathways that allow personally motivating experiences to become bridges for communication. This knowledge may help lead to customized therapies.

With Sidekicks, some children know a parent is behind the curtain, and some don’t, but it doesn’t seem to matter. After a 15- to 30-minute session with the app, children seem more responsive and engaging in person. It’s almost as though they’ve limbered up for the wider conversation, building up their confidence to communicate with people.

The scientific term for the force driving this behavior is ”intrinsic motivation.” It’s about joy — joy defined by the child that is then shared with another.

Ron Suskind is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, and founder and chief executive officer of The Affinity Project, a research and technology company. This article was originally published on Spectrum (www.spectrumnews.org), an online resource which provides comprehensive news and analysis of advances in autism research. Reprinted by permission.

REFERENCES:

1 Robinson J.F. and L.J. Vitale Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 24, 755-766 (1954) PubMed

2 Attwood T. (2003). Understanding and managing circumscribed interests. In Prior M. (Ed.) Learning and behavior problems in Asperger syndrome (pp. 126-147). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Abstract

3 Koenig K.P. and L.H. Williams Occup. Ther. Ment. Health Epubahead of print (2017) Full text